Tunisian Delegation’s Visit to the University Library, University of Cambridge’s Cairo Genizah Fragments

On October 20, 2022 Arabic Poetry in the Cairo Genizah’s Muhammad Imran Khan facilitated a visit with Dr Ben Outhwaite at the University Library, University of Cambridge. The University Library holds almost 9 million items from stone carvings, to sheet music and millennia old scrolls to maps (around 1.5 million in fact, plenty to enjoy for the cartophile) and musty tomes, making it the most important of the over-100 libraries in Cambridge. It is one of the six legal deposit libraries established under the law of the United Kingdom and grows its collection by about 100,000 per year. Additionally, it is also the home of stand-along projects such as the Darwin project and the Cairo Genizah Unit, which is a dedicated research facility that hosts a number of researchers specialising in the Cairo Genizah. It is for this reason that it holds academic reverence for those intrigued by the preservation of intellectual history, culture and the modern techniques employed for these purposes and is thus visited throughout the year by people from all over the world.

Professor Habib Kazdaghli of the Université de Manouba, Tunisia along with the conservator Mme Awatef Bahroun arranged a visit through the Tunisian consulate with Dr Afef Mbarek, a postdoctoral researcher at the School of History, Queen Mary, University of London who is researching the project: “Traces of Jewish Memory in Contemporary Tunisia”. Nine other academics (including graduate students) and conservators from Manouba and Tunis joined the delegation.

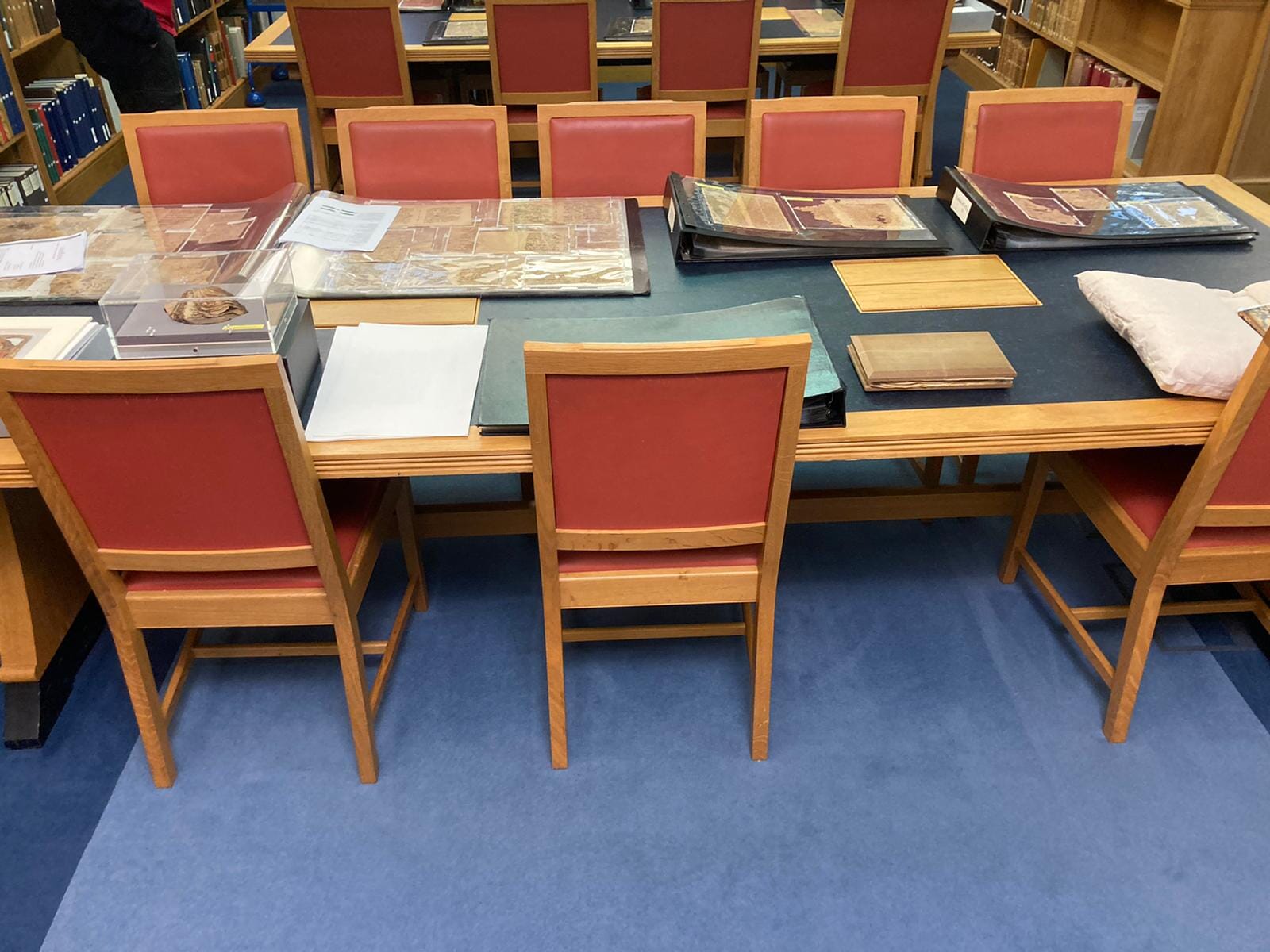

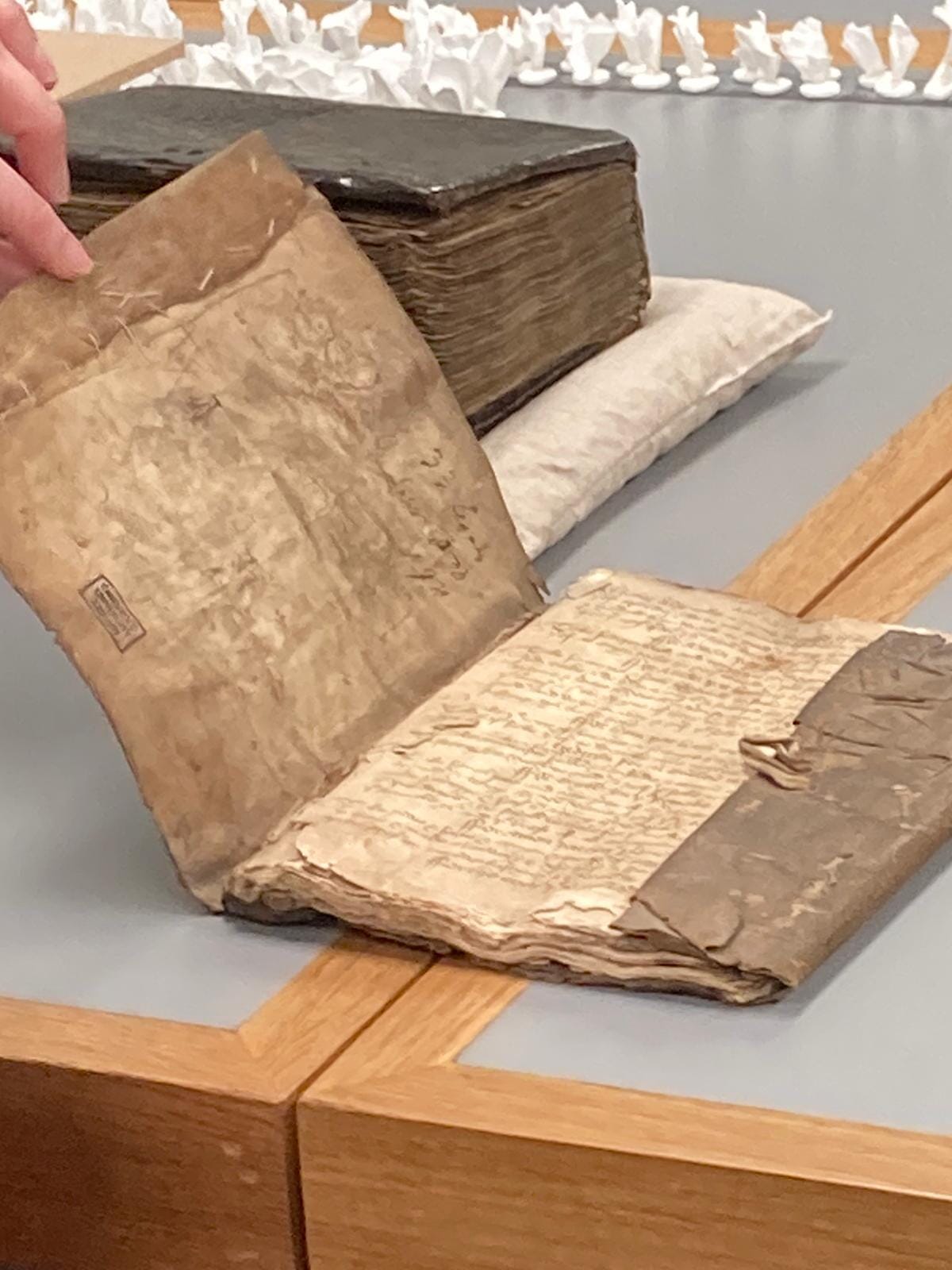

The tour began with a visit to the manuscripts’ reading room, where around two dozen fragments were laid out so that a description of some poignant writings could be shared that would give a varied snapshot of the topics which are covered in the Genizah fragments. Below is a photo of a number of folios, manuscripts and fragments, including a display in a case which shows the condition in which an original fragment would be when it arrived.

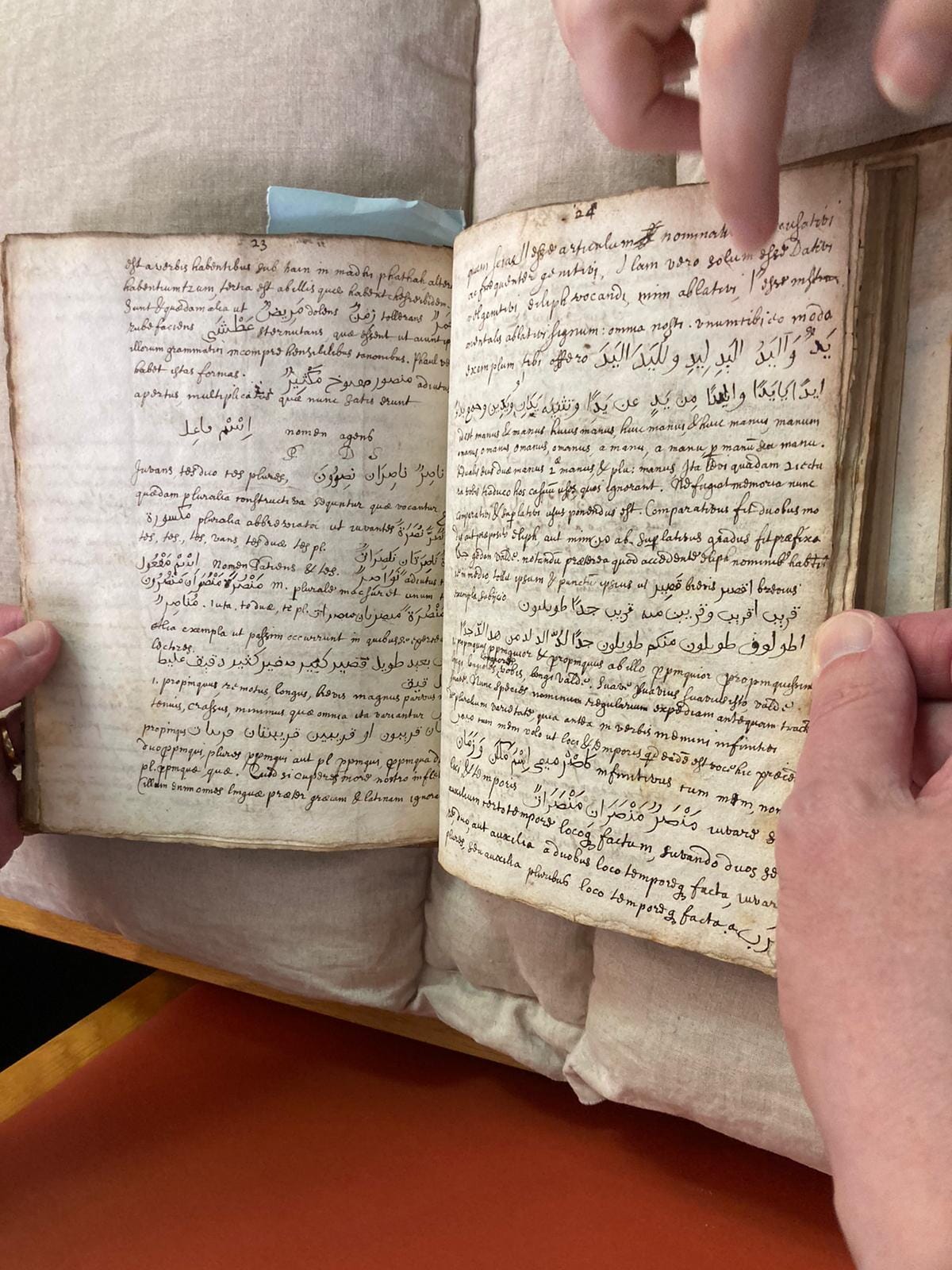

There was also a didactic work written in Latin from the 16th century, which was a work of Arabic syntax. Although it was punctuated by occasional Arabic script, most was written in Latin. It showed the interest in Arabic among Europeans as well as the history of Arabic works in Cambridge, and the University’s long engagement with Arabic as a subject. The penmanship is distinct, lucid and the Latin certainly calligraphic. The Arabic though mature and clear seems to be written by someone who has acquired the language and learnt its orthography. The ink is well preserved and the quality of the paper high, since the pages are intact albeit quite coloured.

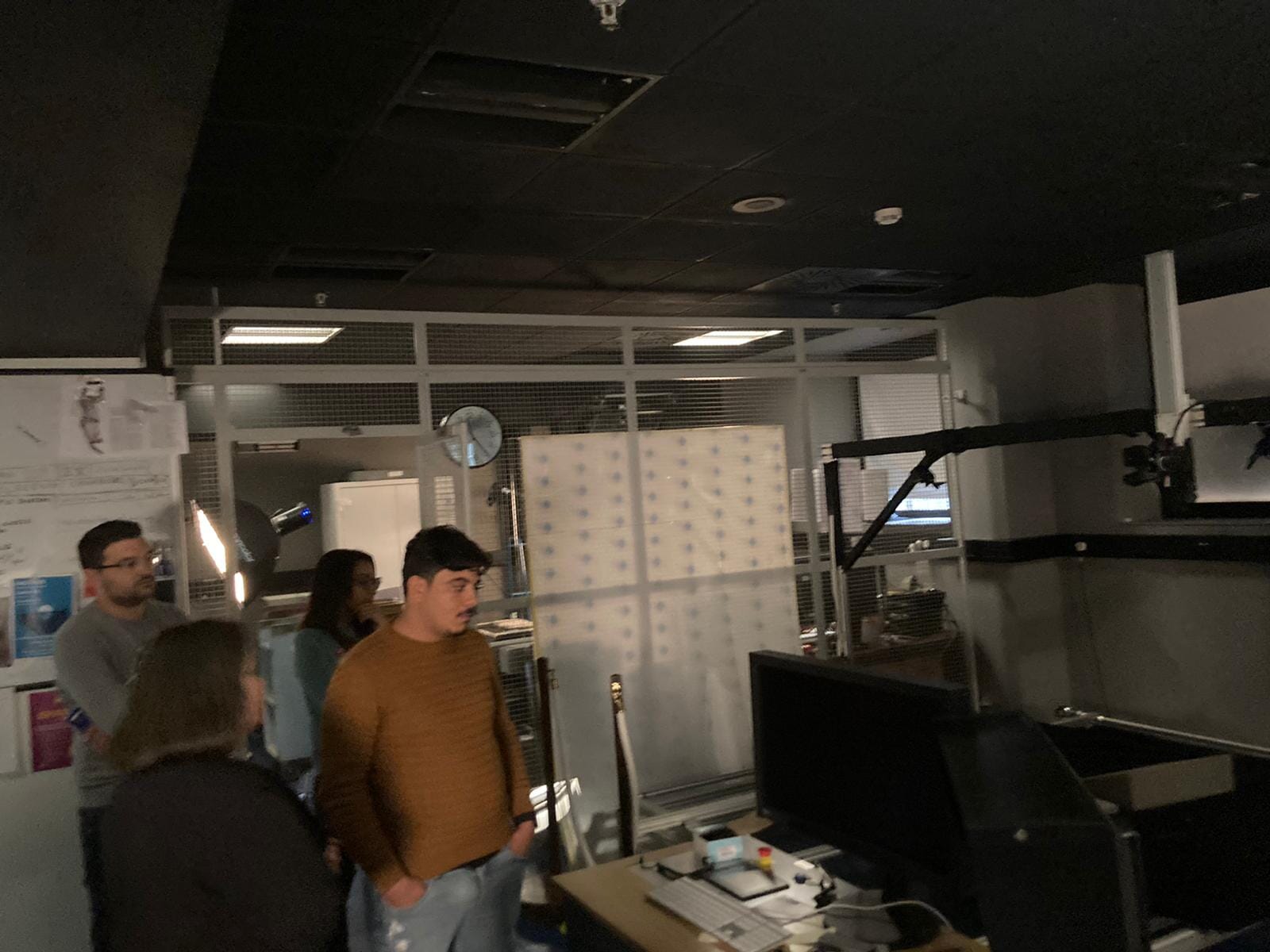

The second part of the tour focussed on going behind the scene where dozens of staff work to repair, digitise and preserve fragments, manuscripts, objects and various other paraphernalia (some dating back several thousand years)! The high level of security is why I would not have been here as a student, as well as the sheer impracticality of such a large-footfall of students being an expensive operation. The shutter beyond which is the metal cage below, is where some of the most expensive works are worked on and will make you realise that security is taken very seriously for the collections.

In the photo on the right, you may also see a large, metal contraption. It is in fact a bespoke made metal frame over an AA size area where maps are processed, laminated and prepared. The area (only partly visible) is so large that the camera rotates on an arm in order for photos to be taken. The five photographers may seem a lot, but if you have done your thesis at Cambridge, you will still have to wait about three years from submission to have your PhD digitised! Rest assured, the hard-working staff are not resting on their laurels, are very dedicated to their jobs and rather congenial.

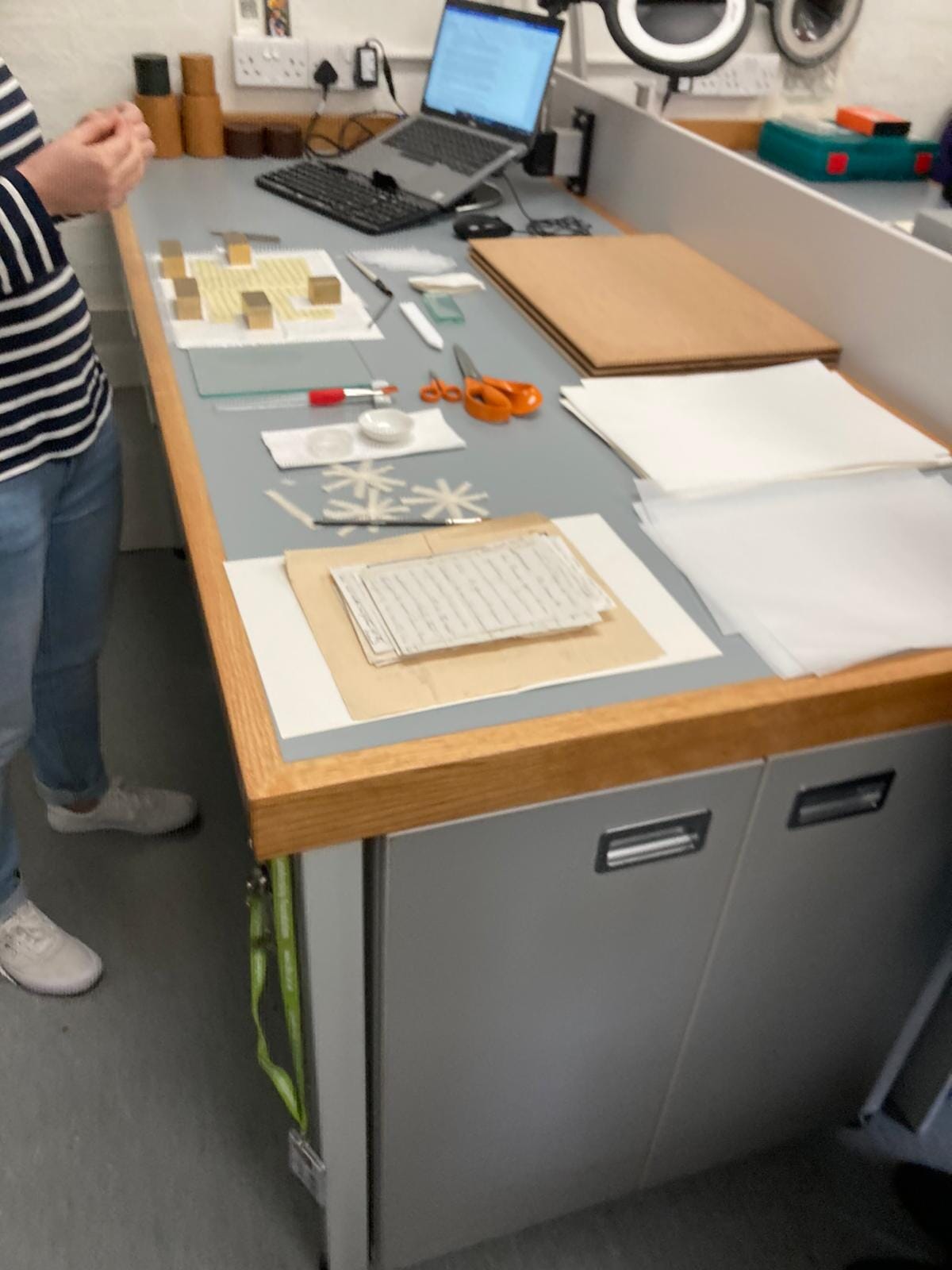

After careful treatment through temperature and humidity control, experts specialised in conservation would then ready the parchment for further preservation, encasement. If the leaf was careworn it would need to be repaired, bound or reinforced delicately with gelatine, starch and other chemicals, applied with a fine brush and then compressed gently with a special weight to affix the repair.

Although the laboratories in the University Library do not do radiocarbon dating, they can employ radio spectral imaging to determine the rough date in which a particular fragment was written. Besides techniques used to repair pages, sometimes specialists in textiles are also brought in through generous funding to preserve the material (often leather) in which a manuscript is bound.