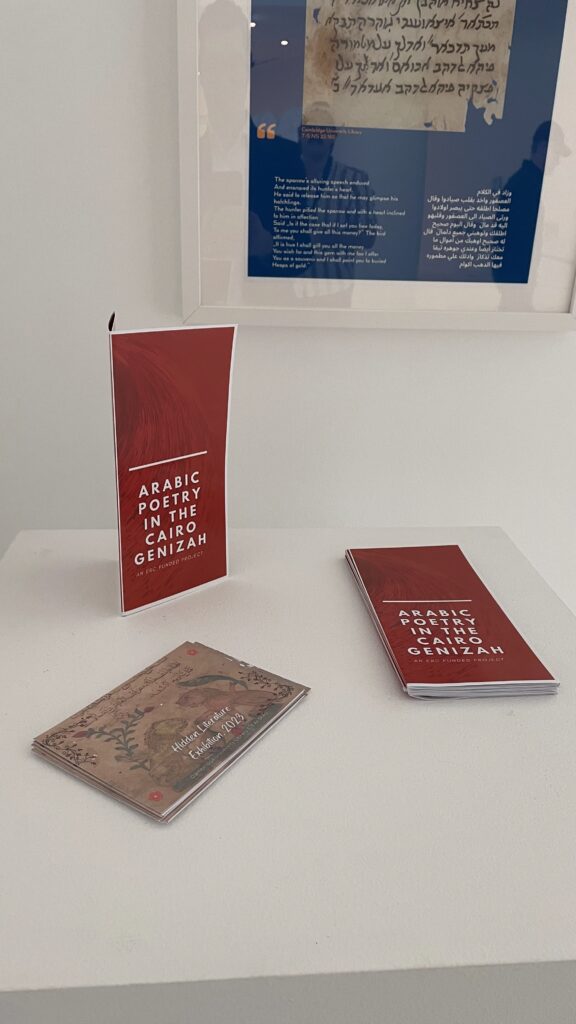

Hidden Literature: APCG’s International Exhibition

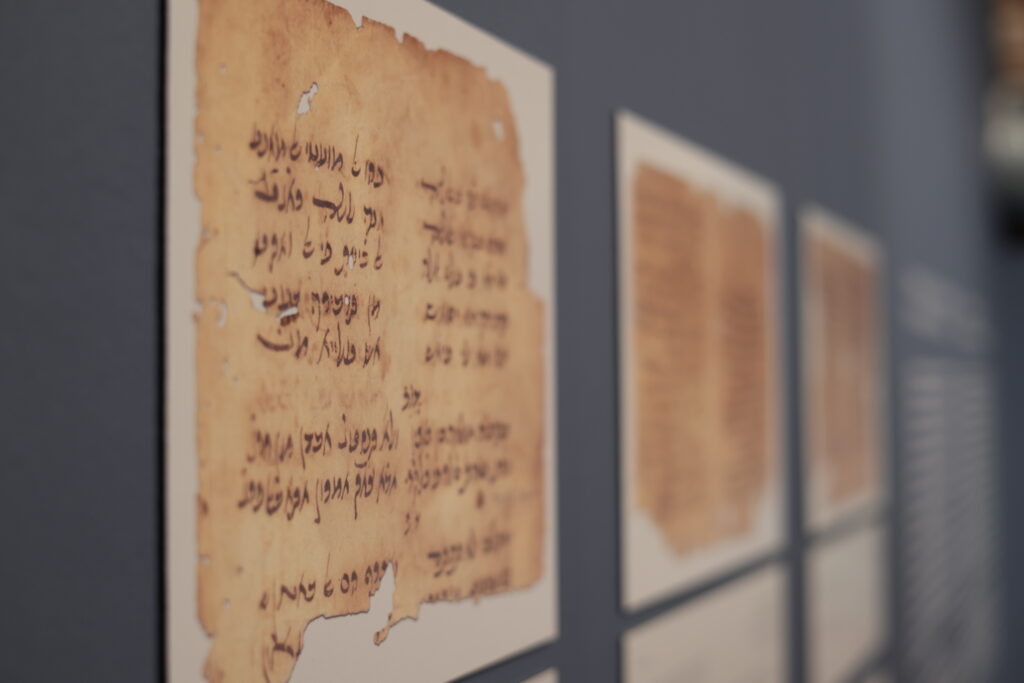

With funding from the European Research Council, in tandem with the generous support from our host partners (Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education, NYU-Abu Dhabi, Dubai International Academic City and Centro Sefarad-Israel), we are proud to present our international exhibition Hidden Literature: Arabic Poetry in the Cairo Genizah. Hidden Literature explores the rich history of the Cairo Genizah, a remarkable collection of medieval manuscripts discovered at the end of the 19th century in a synagogue in Al-Fustat, Old Cairo. This event showcases the significance of the Genizah, extending far beyond the Jewish community of Egypt to the entire medieval Islamic world. We delve into the impactful role of Arabic poetry in the Middle Ages, and how the Genizah has preserved a vast array of Arabic literature, from revered classics to previously unknown poets who utilized the language for religious and secular purposes. Get ready for a series of enlightening talks and a stunning exhibition featuring some of the most exceptional items from the Genizah collection!

Dates

Building Bridges Symposium and Exhibition, Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education, Dundee, Scotland: November, 2022.

Geniza in the Gulf, New York University-Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi: February – March, 2023.

Hidden Literature: Arabic Poetry in the Cairo Genizah, Dubai International Academic City: March, 2023.

We collaborated with Centro Sefarad-Israel for the monumental “The Golden Age of the Jews of Alandalus” in Madrid, Sapin: September 2023 – March 2024.

The exhibition toured to Washington D.C. for the ASMEA annual conference, complemented by an enlightening workshop on the bilingual nature of the texts: November 2023.

We organized a specialized exhibition at the Trinity Long Room Hub in Dublin. This event was attached to our third international conference, “Anthropology of Texts,”: August 2024.

Media Coverage & Public Recognition

Our work has sparked conversations in major media outlets, highlighting the project’s relevance to contemporary culture.

- Khaleej Times Feature: Read how our UAE exhibition changed perspectives on Jewish-Muslim history in the article: “Priceless literature of the medieval Islamic world on display in the UAE.” 👉 [Read the Full Article Here]

- The Cairo Genizah as a Treasury of Arabic Literature Recorded live at the NYU Abu Dhabi Institute (March 9, 2023): In this flagship lecture accompanying our UAE exhibition, Prof Ben Outhwaite (Head of the Genizah Research Unit, Cambridge) and Dr. Mohamed Ahmed (APCG Principal Investigator) explore the hidden literary gems of the Cairo Genizah. The presentation takes viewers on a journey from the dramatic discovery of the manuscripts in a medieval synagogue to the detailed analysis of the texts themselves. Watch as the team reveals how Jewish scribes preserved the masterworks of Arabic poetry—including verses by Ali Ibn Abi Talib and Al-Shafi’i—transcribed in Hebrew script, serving as a powerful testament to the shared cultural heritage of the Middle East. 👉 [Click here to watch the full lecture on YouTube]

- Radio Interview: Listen to APCG team member Prof. Ben Outhwaite discuss the significance of the Genizah and the project’s discoveries on national radio. 👉 [Listen to the Interview Here]

- Blog of the Genizah Research Unit: In collaboration with Centro Sefarad-Israel, our flagship exhibition “The Golden Age of the Jews of Alandalus” achieved monumental success. Running from September 2023 to March 2024, the exhibition drew a final total of 15,000 visitors, far exceeding expectations and demonstrating a massive public interest in the history of coexistence. 👉 Read the Cambridge University Library Report on the 15,000 Visitors Here

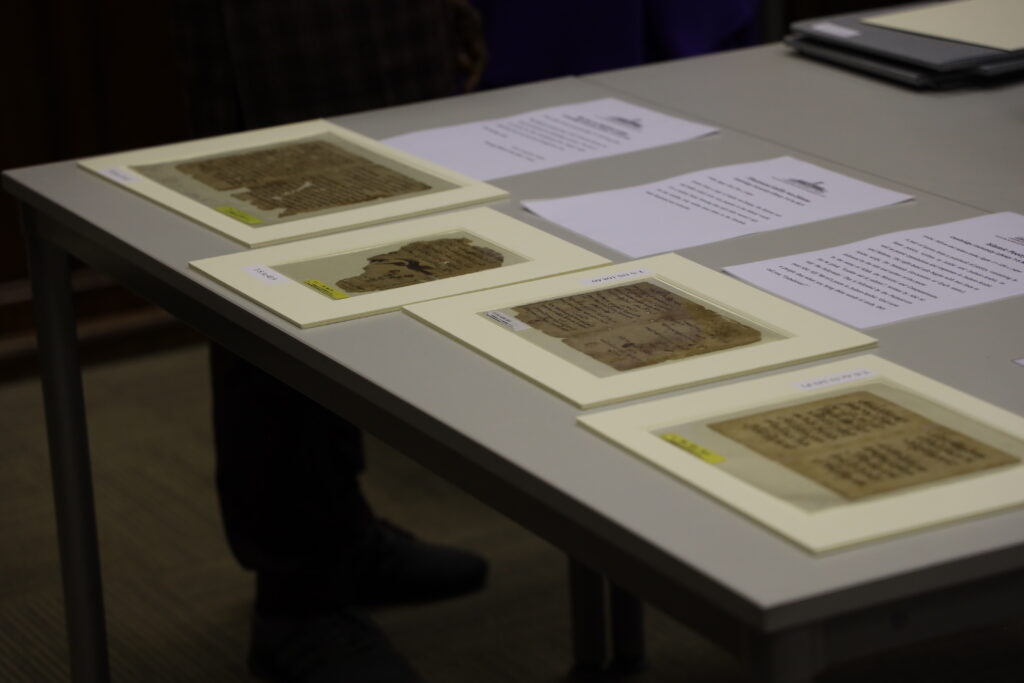

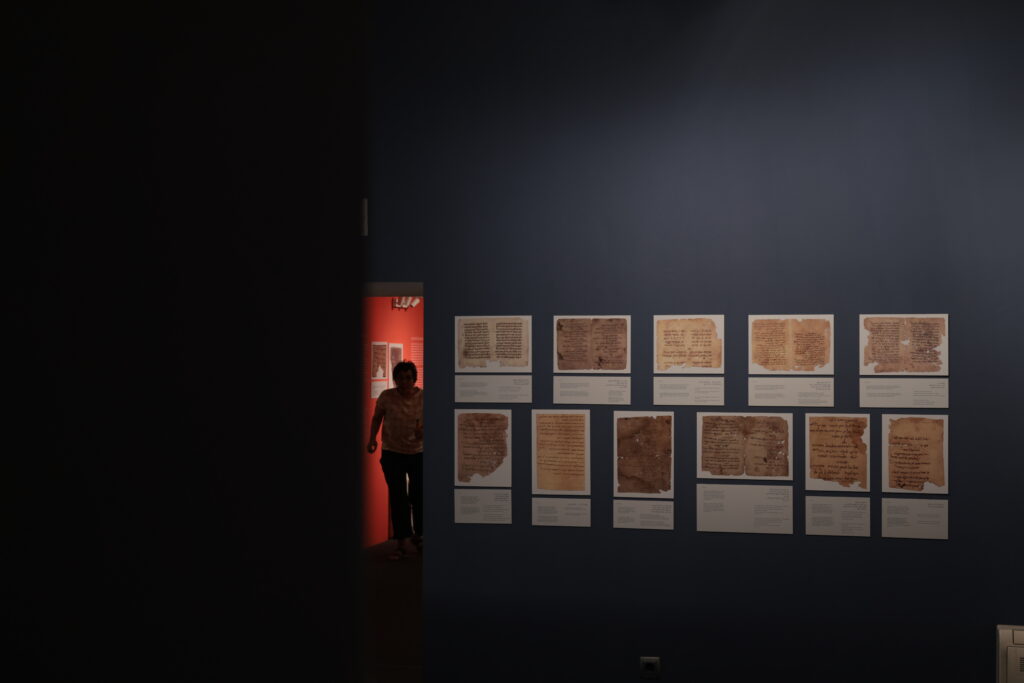

Gallery: The Exhibition Tour

Welcome to the visual archive of our journey. From the record-breaking crowds in Madrid to the intimate workshops in Abu Dhabi and Dublin, this gallery documents the moments where medieval history met modern curiosity. Explore the images below to see how diverse communities across Europe, the Middle East, and the US connected with the shared heritage of the Cairo Genizah.

Exhibition Catalogue

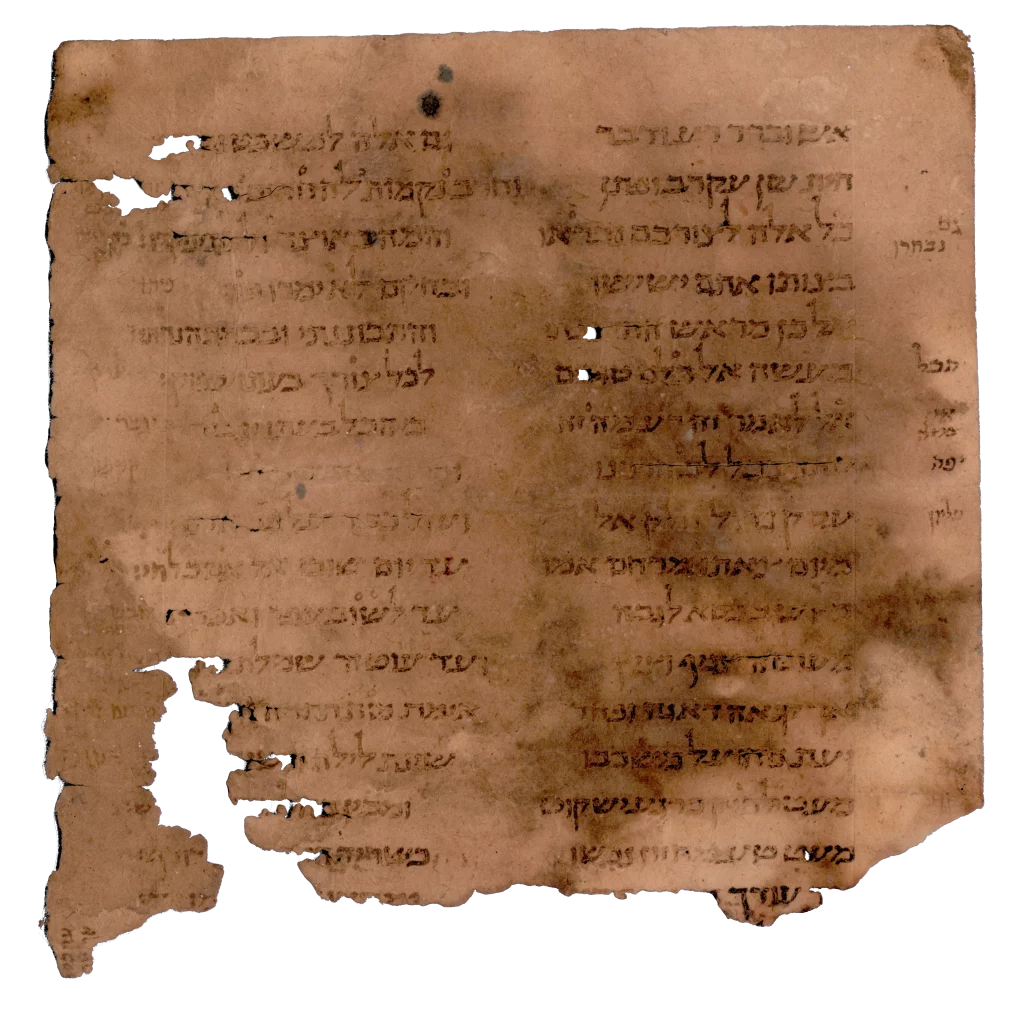

- Cambridge University Library Or.1102

The first Ben Sira manuscript

Paper; Palestine or Egypt; 10th–11th century

This manuscript changed the course of scholarship. It prompted Solomon Schechter to travel from Cambridge to Egypt and retrieve the contents of the Genizah storeroom from the Synagogue of the Jerusalemites in Old Cairo. The book of Ben Sira, known in Christian circles as Ecclesiasticus, was composed in the 2nd century BCE, but its Hebrew text was thought lost in the Middle Ages. In Solomon Schechter’s day, the oldest known version was in Greek translation, and some questioned the existence of a Hebrew original. When Schechter saw that this manuscript preserved a copy of the original Hebrew text, he made plans to track down its source in Egypt.

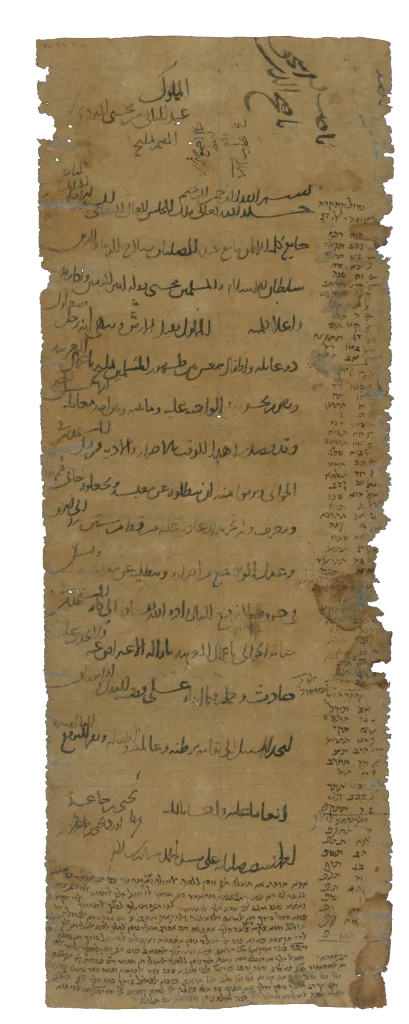

2. Cambridge University Library T-S K2.96 (verso)

Petition to the Ayyubid Sultan Saladin (Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn)

Paper; Egypt; 12th century (after 1174 CE)

All citizens of the Islamic Empire had the right to petition the ruler directly to seek justice. When ʿAbd al-Bāqī, a Jew in the Egyptian town of Malīj found himself in trouble, he petitioned Saladin, the ruler of the Ayyubid Empire, directly and asked for his help. The reverse of the document contains the replies of Saladin’s secretaries, and the whole manuscript has later been reused by a Jewish scribe to write poetry, a calendar and other notes.

Nāṣiḥ al-Dīn Isḥāq. The slave ʿAbd al-Bāqī b. Yaḥyā, the Jew, who resides in Malīj. In the name of God, the merciful and compassionate. May God, the exalted, make eternal the rule of the exalted and lofty seat, the mighty lord, al-Mālik al-Nāṣir, the uniter of the word of the faith, the conqueror of the slaves of the cross, Ṣalāḥ al-Dunyā wa-l-Dīn, Sultan of Islam and the Muslims, reviver of the dynasty of the Commander of the Faithful, cause his power to endure and exalt his word. The slave kisses the ground and reports that he is a poor man with a family and children, who makes his living among Muslims in Malīj in the province of al-Ḡarbiyya. He pays the poll tax for which he is liable and there is no one with whom he has bad relations. Recently he has been hurt and made to suffer by the poll-tax officials. They have summarily made him give up his employment and forced him to work as a tax collector and an informant. There has been no precedent for this for 60 years. The justice of the master should prevent his being caused damage and his being made to give up his livelihood. He asks for the issuing of an exalted rescript, may God increase its efficacy, to all the officials concerned with the collection of the poll tax in the province of al-Ḡarbiyya to release him so that nothing will befall him and to treat his case with justice and impartiality, that he may be able to live in his native town with his family and children. Let the exalted rescript be deposited in his hand, as a kindness and benefaction to him. Praise be to God alone and His blessings be upon our lord Muḥammad, His prophet, and save him.

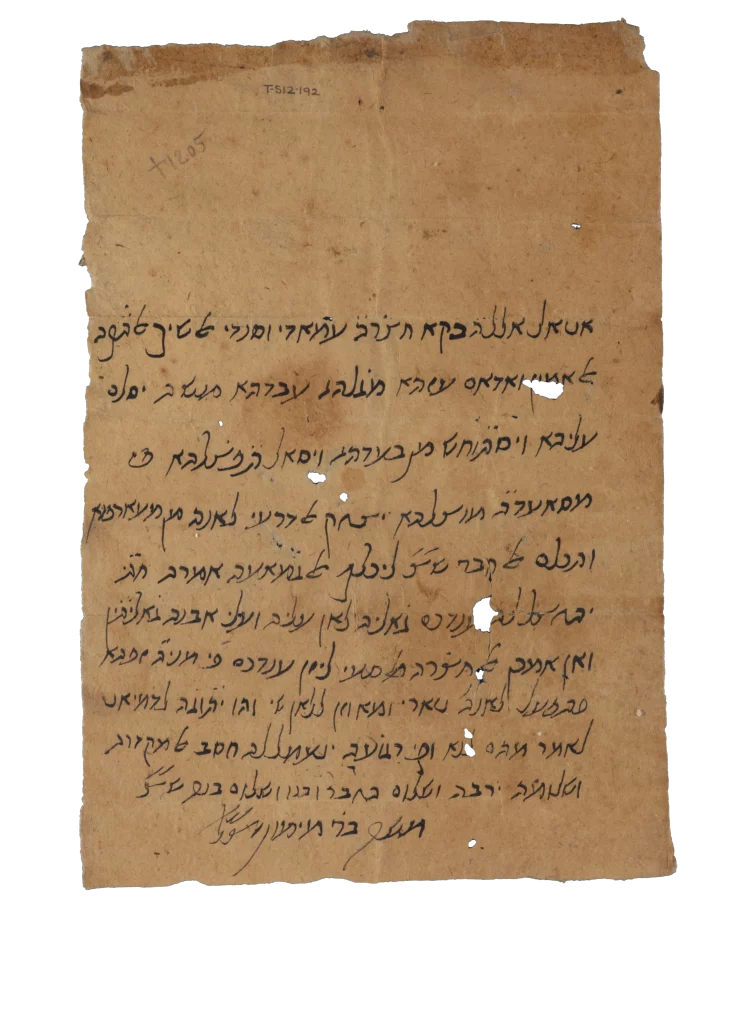

3. Cambridge University Library T-S 12.192

Letter of recommendation written by the Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides

Paper; Egypt; 12th c. (after 1166 CE)

The leading Jewish philosopher of the 12th century, and one of the greatest Jewish thinkers of all time, Moses Maimonides fled persecution in Spain and North Africa to settle in the more tolerant Egypt of the Fatimids and Ayyubids. There he combined the writing of books of Jewish law, philosophy and medicine, with the leadership of the Jewish community and his work as a physician to the Islamic court. Here he writes and signs a letter of recommendation in Judaeo-Arabic (Arabic in Hebrew characters) for a Jewish man who is settling in Egypt. The immigrant will be required to pay the jizya tax to the Muslim authorities, as a member of the ahl al-ḏimma.

May God prolong the life of his honour, my pillar and support, the faithful Sheikh al-Ṯiqa and sustain his position of honour. His servant and admirer Moses sends him greetings. He longs for him because of the distance between them. He requests him to be so kind as to help the bearer (of this letter), Isaac al-Darʿī, because he is one of our acquaintances. May he tell the Ḥaver (a Jewish official) – God preserve him – to entrust his problem to the community and see (the money for) his poll tax collected from among you, because two payments of tax are due from him and from his son. If his honour is able to take steps to have this paid from among you in Minyat Ziftā, then may he do it, for he is a newcomer and he has not yet paid a thing. He is now on his way to Damietta on important business for us, and on his return let there be done on his behalf as much as possible. May his wellbeing increase and the wellbeing of the Ḥaver and his son, and the wellbeing of his own son – God preserve him.

Moses son of the scholar Maymūn – may the memory of the righteous be a blessing.

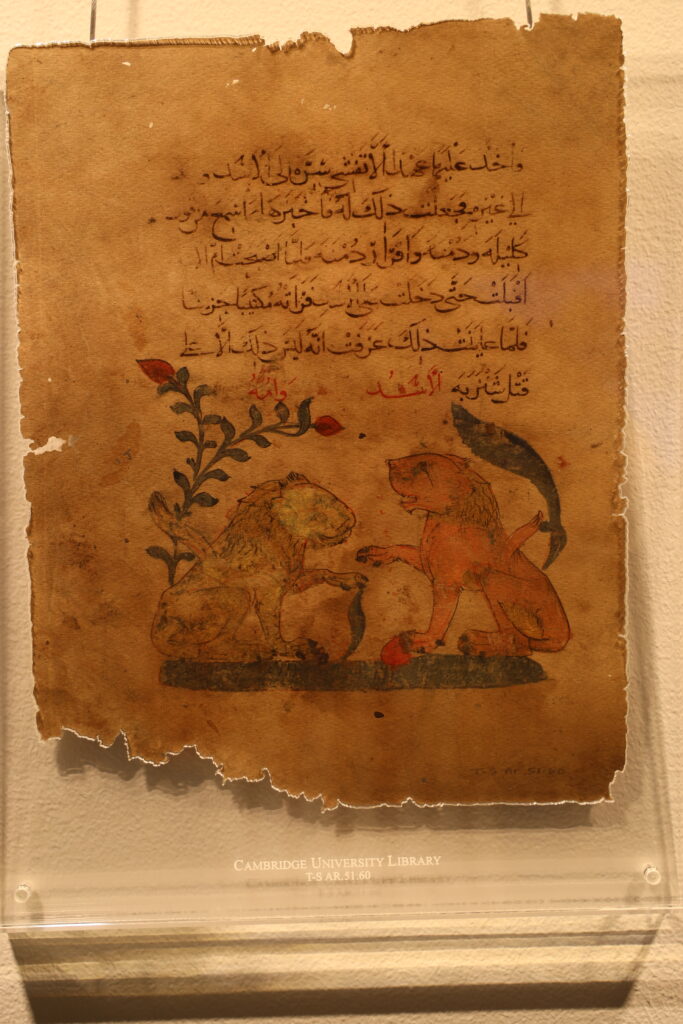

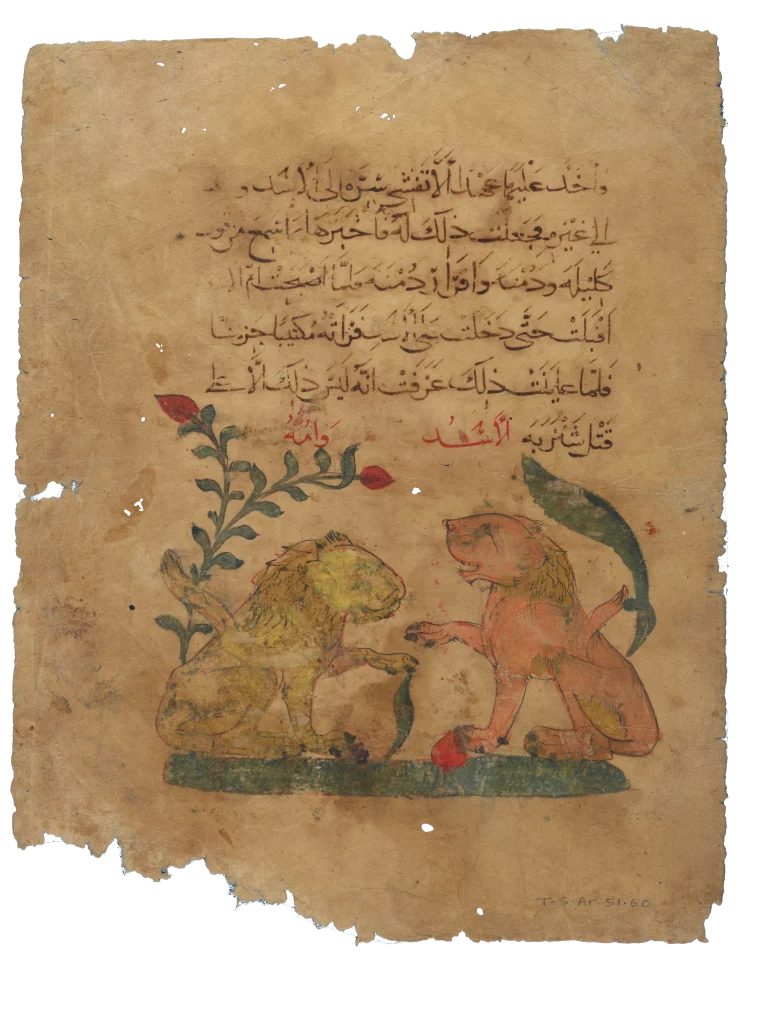

4. Cambridge University Library T-S Ar.51.60

Illuminated leaf of Kalila wa-Dimna, in Arabic.

Paper; Egypt (?); 12th–13th c.

The presence of this fragment of Arabic fables in the Cairo Genizah demonstrates that there were members of the Jewish community of Egypt who were familiar with Arabic literature of the wider Islamic world. Kalila wa-Dimna is composed of dialogues of a moral nature, put into the mouths of animals, and was originally composed in Sanskrit before being translated into Persian and Arabic.

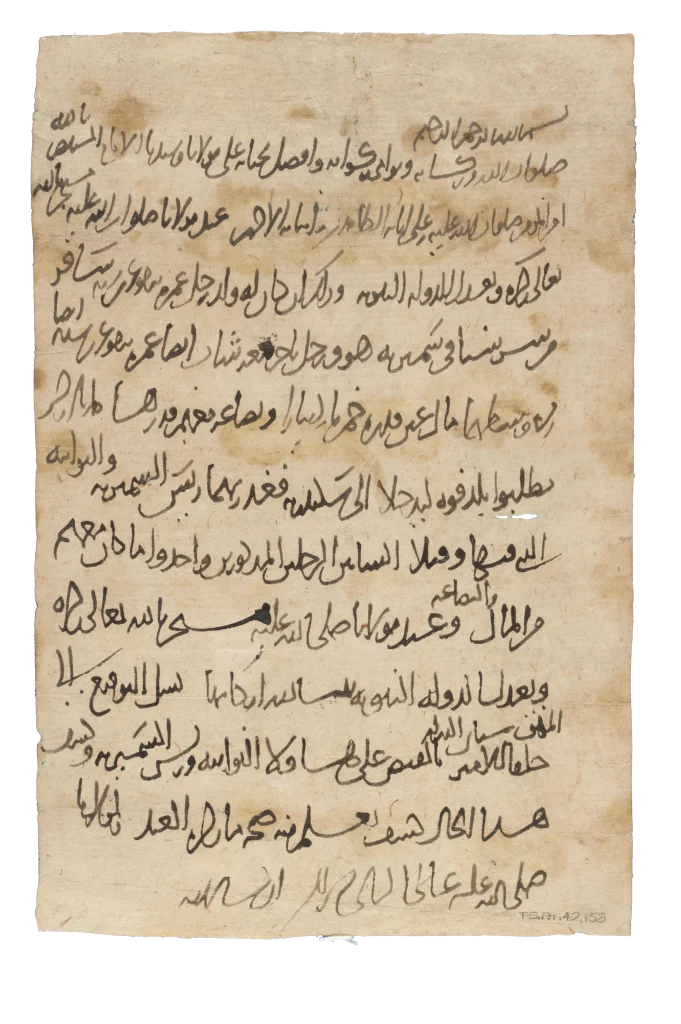

5. Cambridge University Library T-S Ar.42.158

Draft petition to the Fatimid Caliph al-Mustanṣir regarding a murder on a Nile boat.

Paper; Egypt; 1036–1094 CE

This is a draft petition asking the Fatimid Caliph Mustanṣir bi-Allāh to dispense justice by ordering the arrest and investigation of a Nile boat captain and his crew. The petitioner’s son and his colleague had been on a trading trip, and carrying a substantial amount of money and goods, when the boat’s crew murdered them. The writer puts his trust in God and the Caliph to see justice done.

In the name of God, the merciful and compassionate.

The benedictions of God and His blessings, His increasing benefactions and most excellent greetings be upon our master and lord the ʾimām al- Mustanṣir bi-Allāh, Commander of the Faithful, the blessings of God be upon him and upon his pure ancestors and most noble sons. The slave of my master, the blessings of God be upon him, takes refuge in God, of exalted name, and in the justice of the prophetic dynasty, on account of the following: He had a son, a man of twenty-three years of age, who travelled from Sirsinā in a boat, together with a merchant, a young man who was also twenty-three years old. They carried in partnership five-hundred dinars in cash and goods worth two-hundred dinars. They were making for the town of Fuwwa and, from there, to Alexandria. The captain of the boat and the sailors in it betrayed the two aforementioned young men, killed them and took the money and the goods that they were carrying. The slave of our master, God bless him, taking refuge in God, of exalted name, and in the justice of the prophetic dynasty, may God establish its supports, asks for a edict to be issued to the lieutenants of the prosperous ʾamīr, Sinān al-Dawla, to arrest those sailors and the captain of the boat and to investigate this case, so that the truthfulness of what the slave has said be known. To our master, God bless him, belongs the exalted resolution in this matter, if God wills.

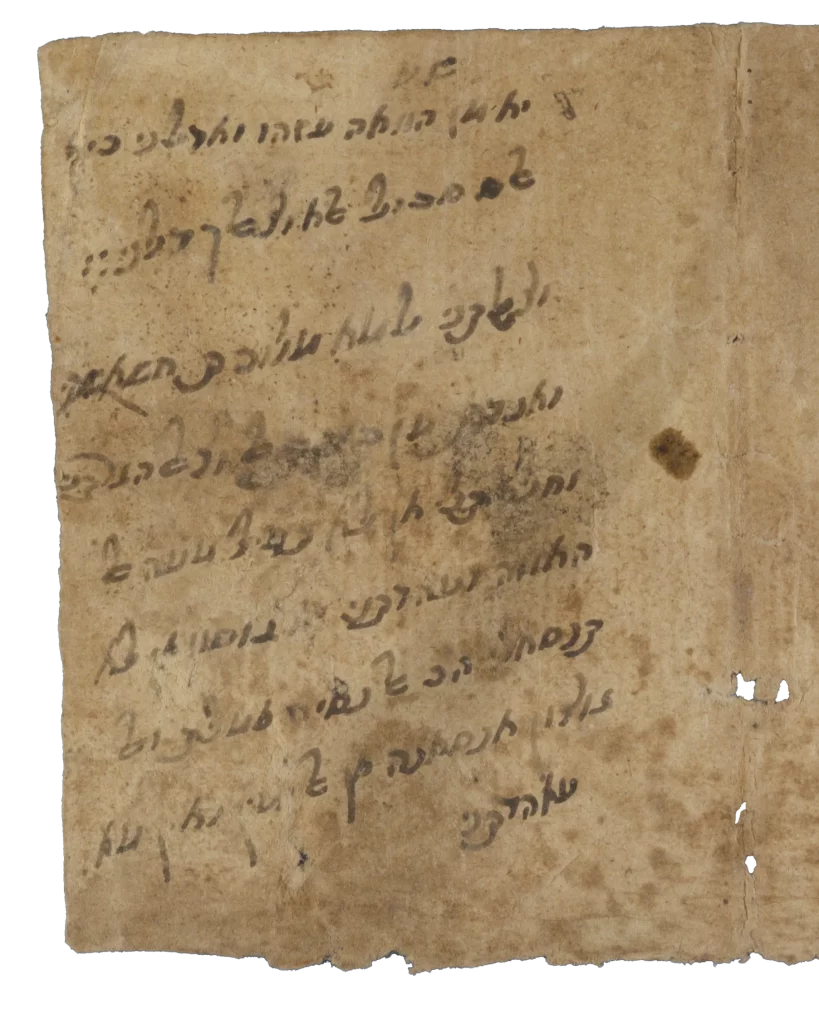

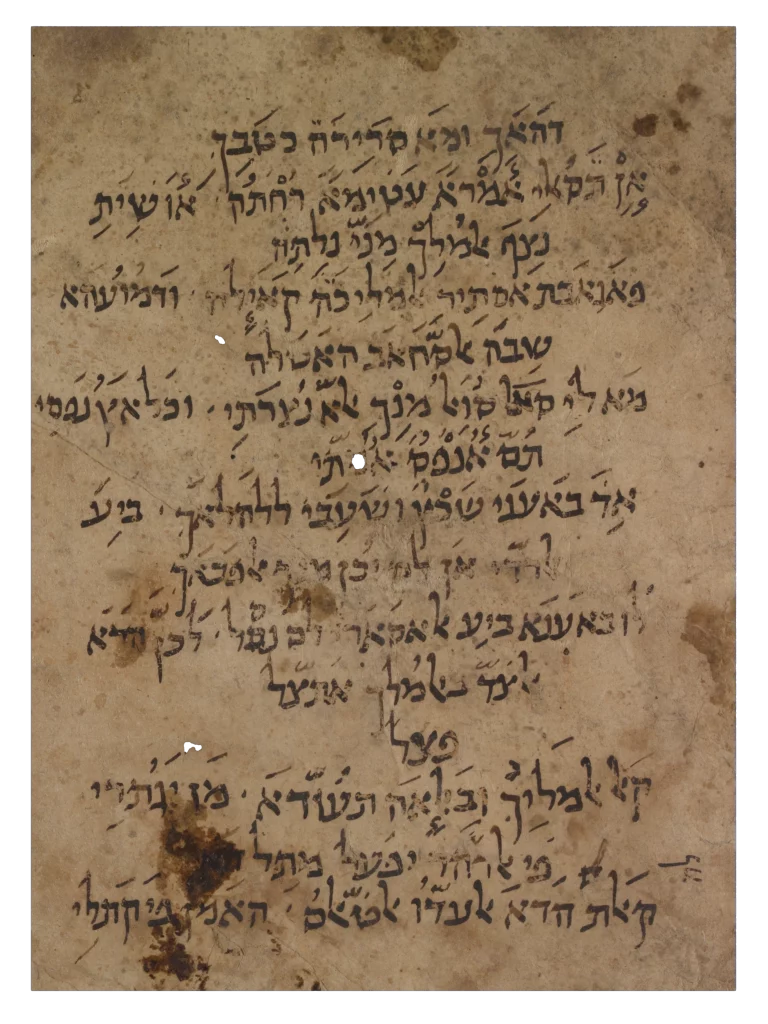

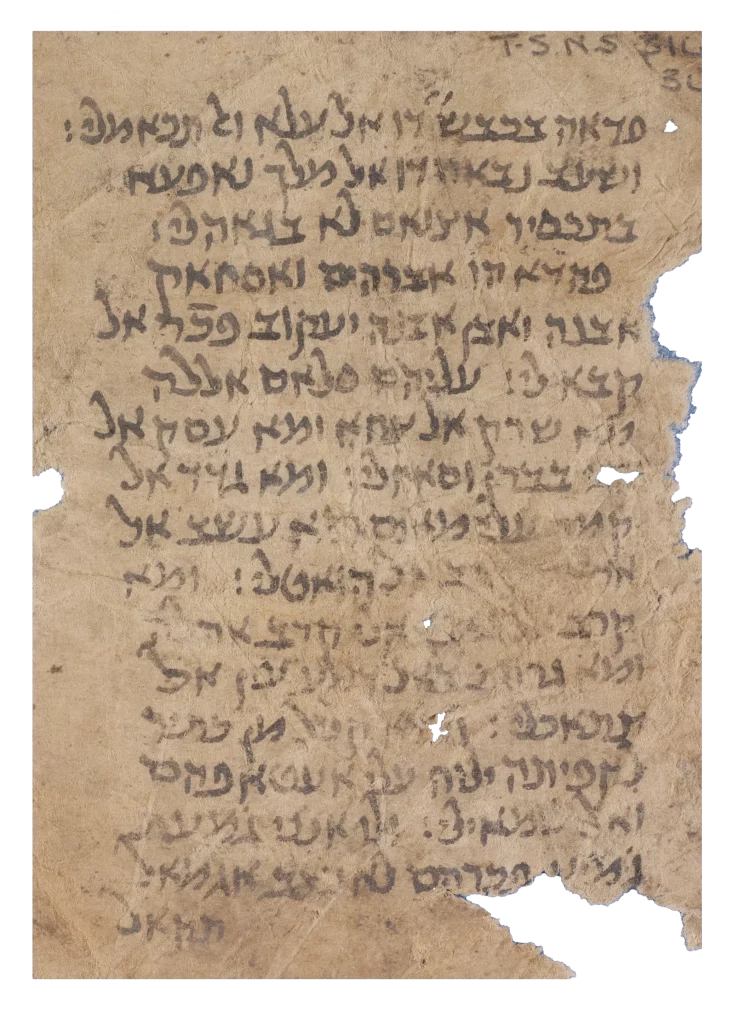

6. Cambridge University Library T-S NS 31.19

A poem attributed to Aḥmad bin Saʿīd al-Busaʿīdī (1710–1783)

Paper; Egypt or North Africa (?); 18th–19th c.

This fragment contains a stanza from a popular poem attributed to Aḥmad bin Saʿīd al-Busaʿīdī (1710–1783), who was the first ruler of Oman. Later, the poem was turned into a song, which was popular in the Gulf region during the early twentieth century. This copy was produced and owned by a member of the Ottoman Jewish community, as the Arabic verse is transcribed into Hebrew script.

يا من هواه أعزه وأذلني كيف

السبيل إلى وصالك دلني

وصالتني لما ملوكت حشاشتي

وأنبت من بـ[عد] الوصال هجرتني

Oh, the one whose love strengthened him and humiliated me –

What is the path to reach you? Guide me!

You were intimate with me when you owned my last breath of life,

But you once again forsook me after reunion

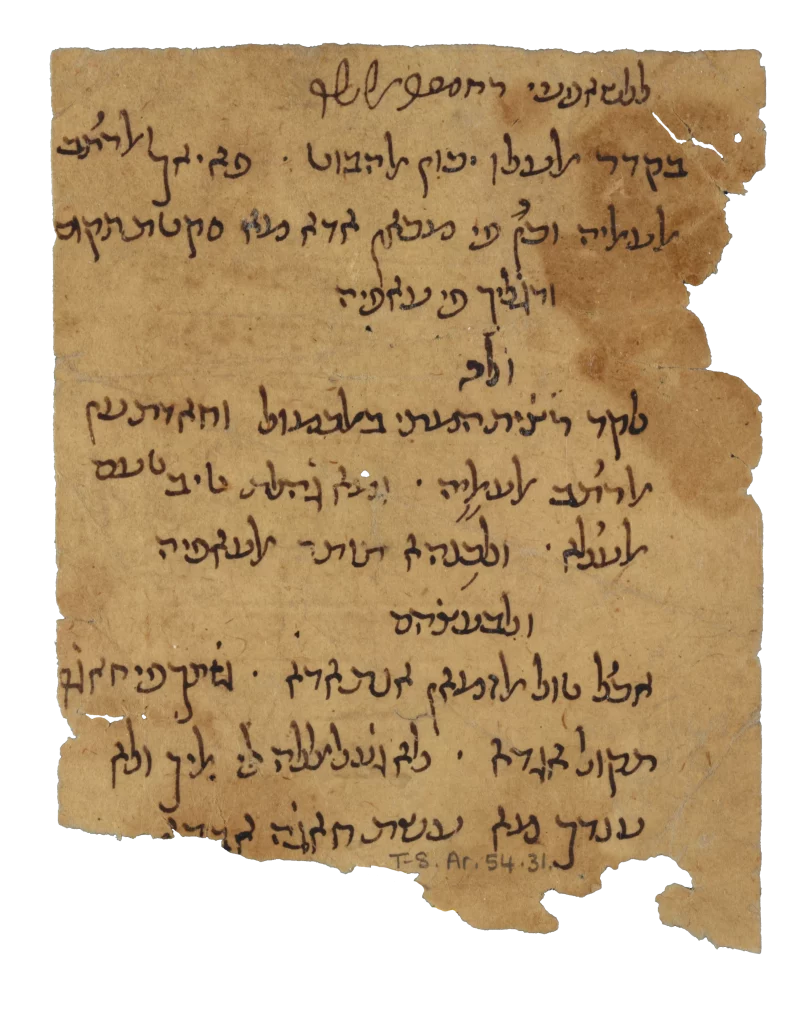

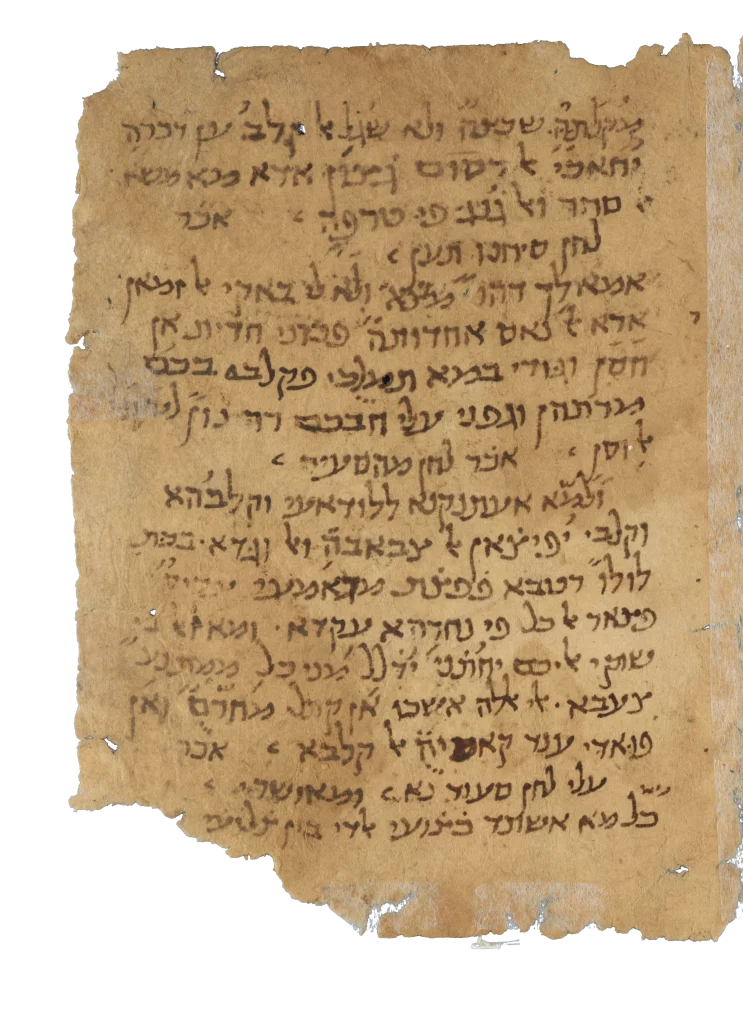

7. Cambridge University Library T-S Ar.54.31 (verso)

A poem attributed to the Muslim thinker al-Shāfiʾī (767–820 CE)

Paper; Egypt; 12th–13th c.

This fragment shows Jewish interest in Classical Arabic poetry, as it transcribes into Hebrew script an Arabic poem that it identifies as being by the great Muslim theologian, jurist and thinker, al-Shāfiʾī. The first line has, in Hebrew script, the typical approbation on a revered scholar.

للشافعي رحمه الله

بقدر العلو يكون الهبوط فاياك والرتب

العاليه وكُن في مكان اذا ما سقطت تقوم

ورجليك في عافيه

From the sayings of al-Shāfiʾī – may Allah’s mercy be upon him:

According to one’s ascent, will be the fall,

So be wary of lofty ranks, and be in a position, should you fall, you may rise

while sturdy-footed in health

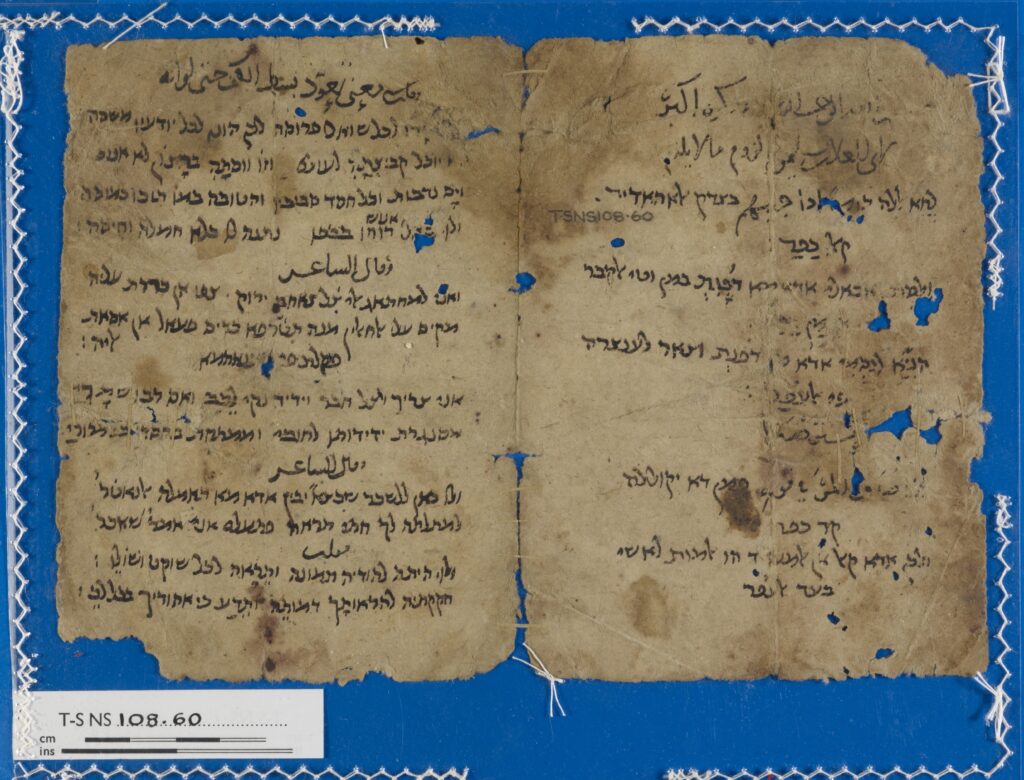

Cambridge University Library T-S NS 108.60 (verso)

A poem attributed to Abū ʿAlāʾ Al-Maʿrrī (973–1057 CE)

Paper; Egypt; 11th–12th c.

This fragment contains poetry in Arabic in Arabic script, Arabic in Hebrew script, and in Hebrew itself, and was from a notebook of a Jewish poet or cantor. It opens with a poem by the Fatimid poet Abū l-ʿAlāʾ al-Maʿrrī, beginning with the verse لَحا اللَهُ قَوماً إِذا جِئتَهُم. Some verses in the poem are written in Arabic script, side by side with poetic responses in Hebrew script.

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم يكون أكبر

لابي العلاء بن سليمن لزوم مالا يلزم

لَحا الله قَوماً إِذا جئتهُم بصـدق الأَحاديث .

:قالوا كفر

ولست أبالي إِذا ما دُفنِتْ بمن وطئ القبـر

:[أَو] مَن [حَفَر]

In the name of Allah, the Merciful and Compassionate, He is the greatest

“Luzūm mā lā yalzamu”, written by Abū al-ʿAlāʾ Ibn Sulaymān

God curse a people, if you bring to them statements of truth,

They say: “he has disbelieved”

Yet on my interment, indifferent am I, to whom upon my grave steps

Or who digs it

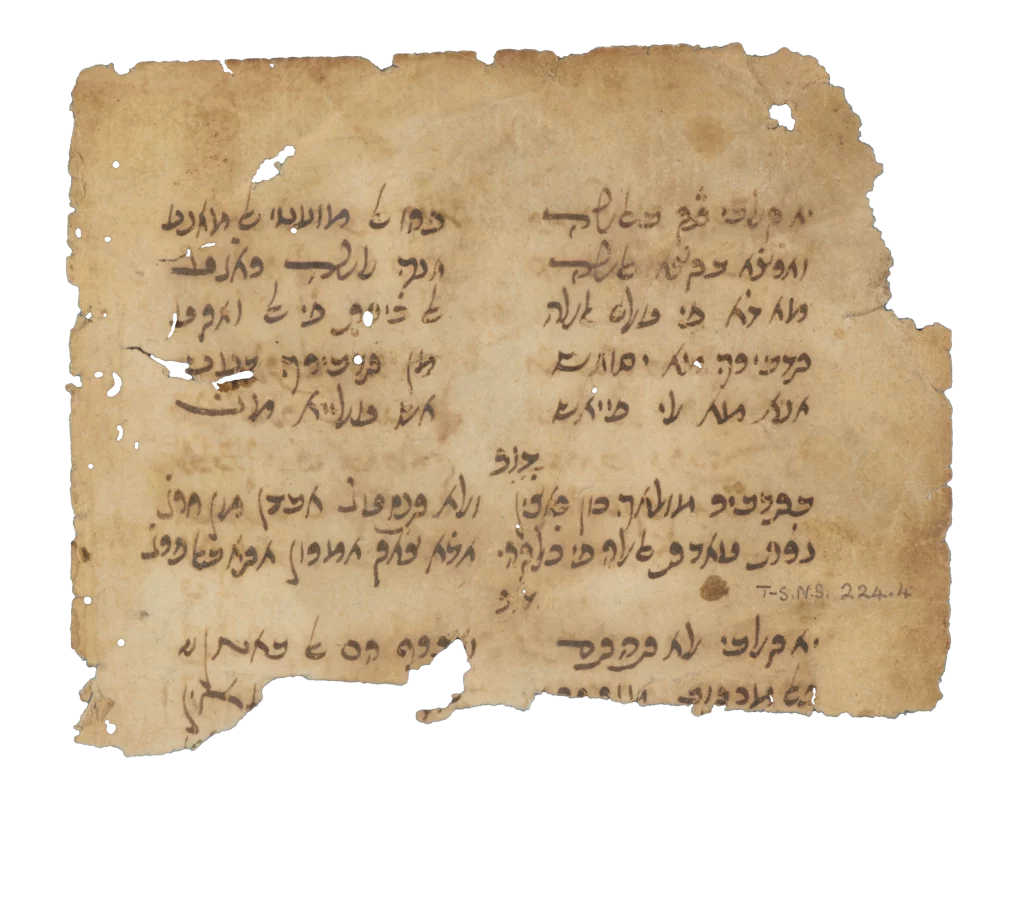

9. Cambridge University Library T-S NS 224.4

Al-Fiyyāshiyya, a Sufi religious poem.

Paper; Egypt or North Africa; 16th–17th c.

This fragment includes a collection of Sufi religious poems called the Fiyyāshiyya (الفياشية), in Hebrew script, showing Jewish interest in Sufi thought and culture. Sufi Fiyyāshiyya poetry was prevalent among the Sufi people of the Maghrib, who used to sing it using Andalusian drums. It is considered one of the masterpieces of Moroccan colloquial poetry, which is attributed to the 16th-century righteous saint ( = الولي الصالحal-walī al-ṣāliḥ) Sidi ʿUthman Ibn Yaḥya al-Sharqī, who was known as Bahlūl al-Sharqī. The poem here demonstrates the ascetic mode of the Sufi school in Islam, which shows complete contentment with God’s decree. The poet expresses his happiness, satisfaction of and trust in Allah, the everlasting Protector of the Glory, the Generous and Forbearing God.

يا قلبي ثق بالله فهو الموعطي المانع

وارضا بقضا الله انك لله راجع

ماذا في علم الله الخيرات في الواقع

Oh, my heart, trust in Allah. He is the Giver, the Preventer

And you should be pleased with Allah’s decree. Indeed, to Allah you are submissive.

What is confined to the knowledge of Allah? The virtues in reality.

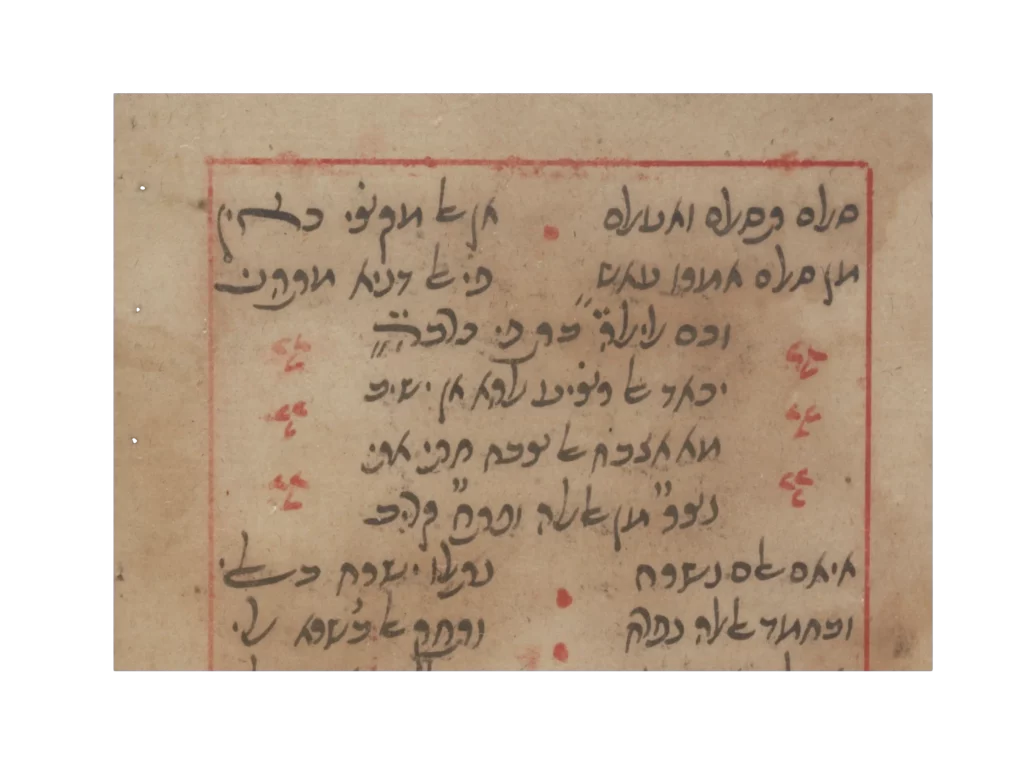

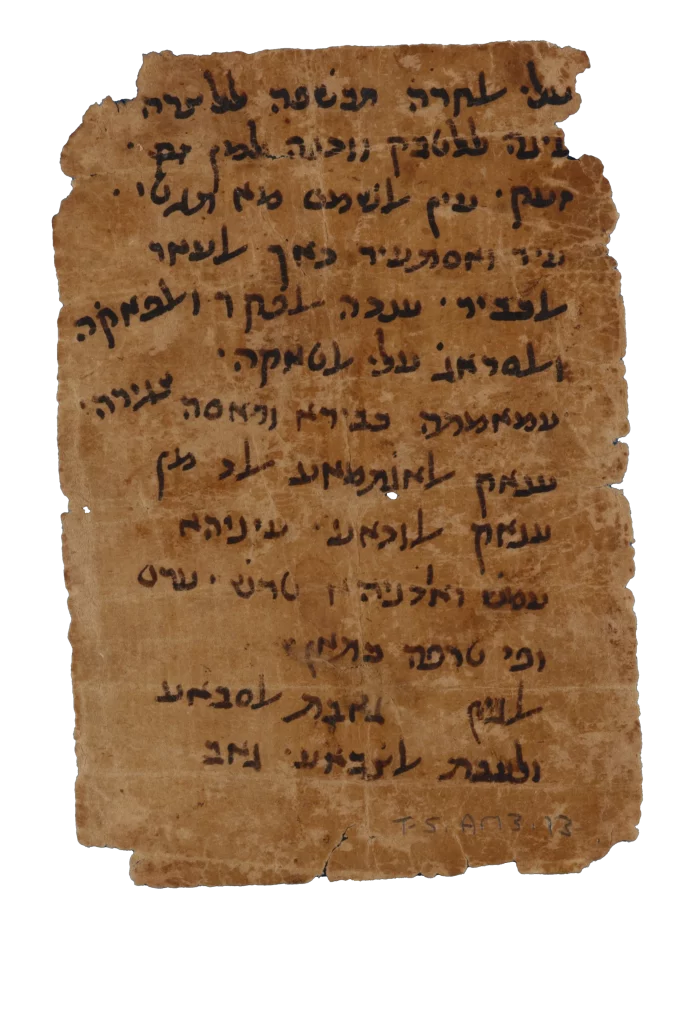

- Cambridge University Library T-S Ar.37.239 (verso)

An Arabic poem calling for peace, by an unknown poet

Paper; Egypt or North Africa; 17th–18th c.

This otherwise unknown Arabic poem seeks to calm the anxieties and worries that befall most people at some stage in their life. The remarkable feature of this poem is that it is “Jewish” literature, at least to the extent that it was written by a Jew in Hebrew script (but Arabic language) for a Jewish readership. However, we cannot be sure as to whether the original author of the Arabic poem was a Muslim or a Jew, and it demonstrates the universality of the challenges that faced people, no matter what their religion. Particularly interesting is the use of Islamic tropes to promote well-being, with a literary reference to hope from a Qur’anic passage – copied out in Judaeo-Arabic by a Jew for a Jewish audience in a Muslim-majority land. Such fragments show the diverse cultural milieu of the pre-modern Islamicate world.

سلم تسلم واعلم ان الـ مقضي كاين

من سلم امرو عاش في الـ دنيا متهني

∵ وكم ليلةً بت في كربةٍ ∵

∵ يكاد الـ رضيع لها ان يشيب ∵

∵ ما اصبح الـ صبح حتى اتى ∵

∵ نصرٌ من الله وفتحٌ قريب ∵

أيام الم نشرح نتلو يشرح بالي

وبحمد الله نفرح وتحق البُشرا لي

Submit and you will be at peace and know that one’s fate is unavoidable.

Whoever submits in his affairs will live pleasantly in the world.

How many a night did you spend with a worry

(which caused) the suckled infant almost to become grey-haired?

It did not become morning until there arrived

Help from God and victory was at hand.

The days when we recite “alam nashraḥ” my chest puffs out,

And with the praise of God we are pleased and glad-tidings are assured for me.

11. Cambridge University Library T-S NS 188.7

The story of the Jewish queen Esther in poetic form

Paper; Egypt (?); 12th–13th c.

The story of the Persian Queen Esther, from the biblical book of Esther, is associated with the Jewish festival of Purim, when the community celebrates their deliverance from a plot by the evil courtier Haman, who planned to massacre all the Jews of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. This Judaeo-Arabic poem was probably to be recited or sung at the festival.

فَأجِابَت أَستِير الملِيكَةَ قَائِلَه وَدُموعَها

شِبَه السَّحَاب هَاطِله

مَا لِي سُوَالُ مِنْكِ إلّا نُصرَتِي. وَخَلاصُ نَفسِي

مّ أَنْفُسَ أُمّتِي

Esther, the queen, replied with tears

like rain from clouds:

“I have no request from you but defending me, and

Rescuing myself and my people!”

12. Cambridge University Library T-S NS 314.34

A poem by the Arabian Jewish poet al-Samawʾal bin ʿĀdiyā (d. 560 CE)

Paper; Egypt (?); 12th–13th c.

This fragment is part of a long Arabic poem, in Hebrew script, in the Ṭawīl poetic metre, that belongs to the genre of ‘poetry of enthusiasm’, in which the poet praises the history of the Jewish people. The verses are possibly drawn from the Arabian Jewish poet al-Samawʾal bin ʿĀdiyā, as they are similar to another long poem of his, an ode which begins with the verse: ألا أيها الضيف الذي عاب سادتي “ʿalā ayyuhā al-ḍayf alladhī ʿāba sādatī”, in which he specifically narrates the stories of the prophets Abraham, Isaac and Joseph. The poem starts with glorifying the “master”, Isaac, for whom God (Almighty and Exalted) sacrificed a sheep, and goes on to recall the ancient past of the Jewish people and their prophets, Ibrāhīm (Abraham), Isḥāq (Isaac) and Yaʿqūb (Jacob), Mūsa (Moses), and Yosef (Joseph). There are also references to the River Nile and Mount Sinai (Ṭūr Saynāʾ).

ونحن بني اسرايل والسيد الدي

:فداه بكبش دو العلا والتكاملي

وشعب نباه دو الملك نافعا

:بتكسير اصنام لا بجاهلي

And we are the nation of (Prophet) Israel, and the master whom

He, Almighty and Exalted, sacrificed a sheep for him,

And a nation whom the Lord elevated for benefit,

By destroying idols, not through idolatry.

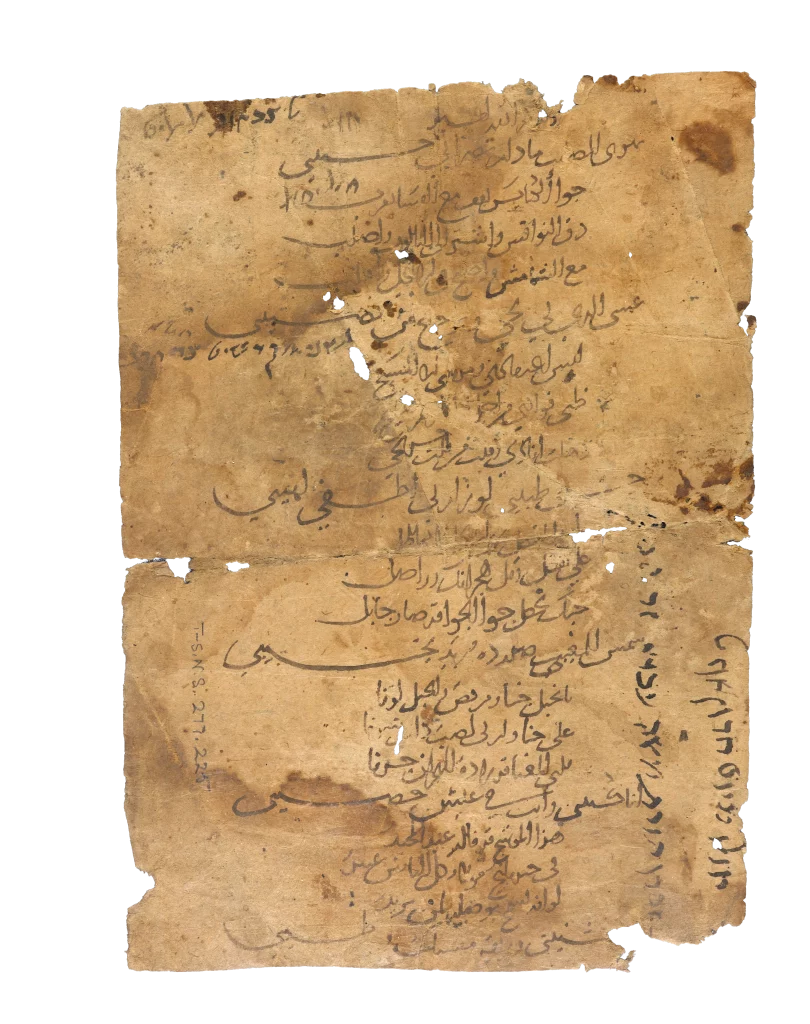

13. Cambridge University Library T-S NS 277.225 (verso)

A Christian poem by a poet known only as ʿAbd al-Majīd

Paper; Egypt (?); 16th c. or later

This fragment holds Christian religious poetry written in the muwashshaḥ style, in Arabic script, possibly in the Egyptian Arabic dialect. The poem seems to have been written by a poet called ʿAbd al-Majīd, as conveyed in the latter verses of the poem. The poet glorifies Jesus and those who adore the Cross, and refers to Christian rituals of evening and morning prayers in the Church. The presence of Hebrew script on the fragment shows that it had, at one point, a Jewish owner, again demonstrating the interwoven nature of the Islamicate cultural world.

يهوى الصليب ما دام نصراني حسيبي

جوا الكنايس يقف مع المسا يقرب

دق النواقس واشر الى التالوت واصلب

مع الشماس واصبح في الهيكل واصلب

He adores the Cross as long as he is a esteemed Christian

Inside the churches he stands up as evening approaches

Ring the bells, point to the Trinity and make the sign of the Cross

In the presence of the deacon, get in the altar in the morning and pray

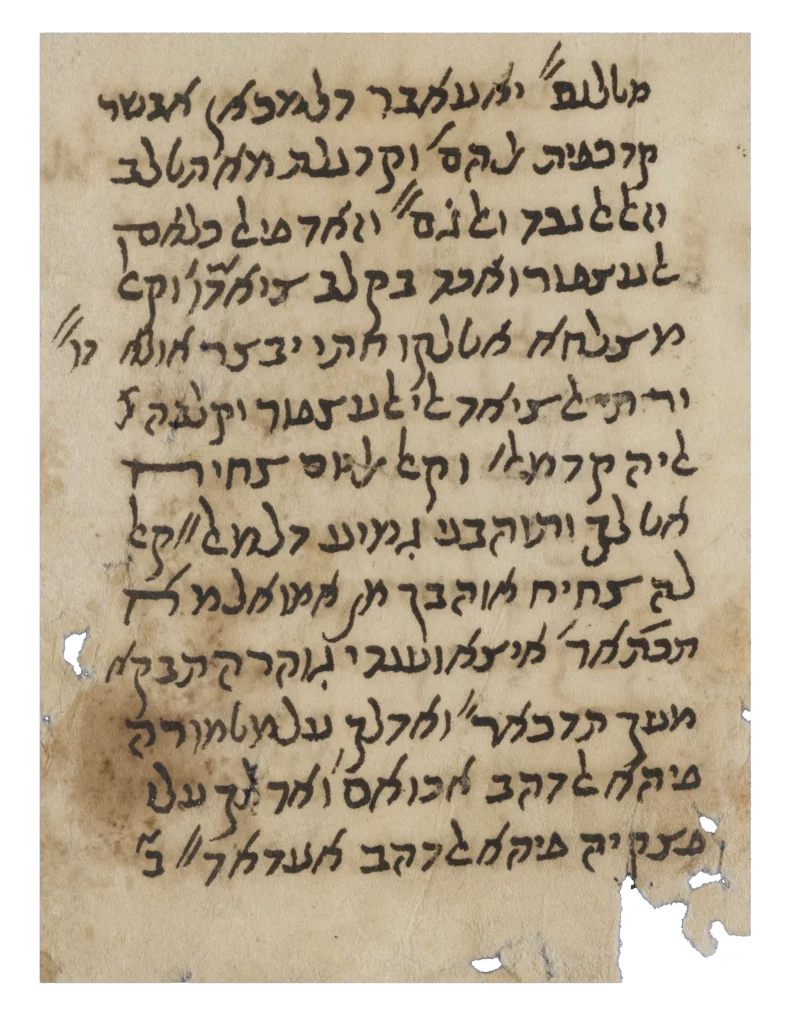

14. Cambridge University Library T-S NS 33.160

The story of the Hunter and the Sparrow

Paper; Egypt or North Africa; 17th c. or later

The theme of the hunting or snaring of the sparrow (al-ʿuṣfūr) has a long history in Arabic literature, and became especially popular in the 17th-c. Here, in this Judaeo-Arabic version, the sparrow attempts to talk his way out of the snare in which the hunter has trapped him, by promising him gold, jewels and buried treasure.

وزاد في ال كلام

العصفور واخد بقلب صيادوا وقال

مصلحا اطلقه حتى يبصر اولادوا

ورتى الصياد الى العصفور وقلبهو

اليه قد مالﹶ وقال اليوم صحيح

اطلقك وتوهبني جميع دلمالﹰ قال

له صحيح اوهبك من أموال ما

تختَارَ أيضا وعندي جوهره تبقا

معك تذكارﹰ وادلك علي مطموره

فيها الدهب اكوام

The sparrow’s alluring speech endured

And ensnared its hunter’s heart.

He said to release him so that he may glimpse his hatchlings.

The hunter pitied the sparrow and with a heart inclined to him in affection

Said “Is it the case that if I set you free today,

To me you shall give all this money?” The bird affirmed,

“It is true I shall gift you all the money

You wish for and this gem with me too I offer

You as a souvenir and I shall point you to buried

Heaps of gold.”

15. Cambridge University Library T-S Ar.13.13

Proverbs in colloquial Egyptian Arabic

Paper; Egypt; 13th c. or later

This Hebrew-script fragment records a selection of proverbs in Egyptian Arabic dialect (including a version of ‘when the cat’s away, the mice will play’, but with lions and hyenas), organised by the Arabic alphabet.

على الحرّة تكشفه للصره.

عينها على الطبق ودنها لمن زق

زعق. عين الشمس ما تغطي.

عير واستعير بان العار

الكبير. عنده الفقر والفاقه

والسراج على الطاقه.

عمامته كبيره وراسه صغيره.

عناق الاجتماع ألد (ألذ) من

عناق الوداع. عينيها

عمش وأوذنيها طرش. عرس

وفي طرفه ختان

الغين غابت السباع

ولعبت الضباع.

For virtuous women undress (yourself) till the navel.

On the plate are fixed her eyes, her ears are

opened to whoever cries. The eye of the sun cannot be covered.

Borrow and lend out, the great

shame has appeared. He is poor and has low income,

though he puts a lamp in his niche.

His turban is big, and his head is small.

A meeting hug is better

than a farewell hug. Her eyes are

blind and her ears are deaf. A wedding,

and afterwards a circumcision.

Letter ḡayn (when) the lions went away,

the hyenas played.

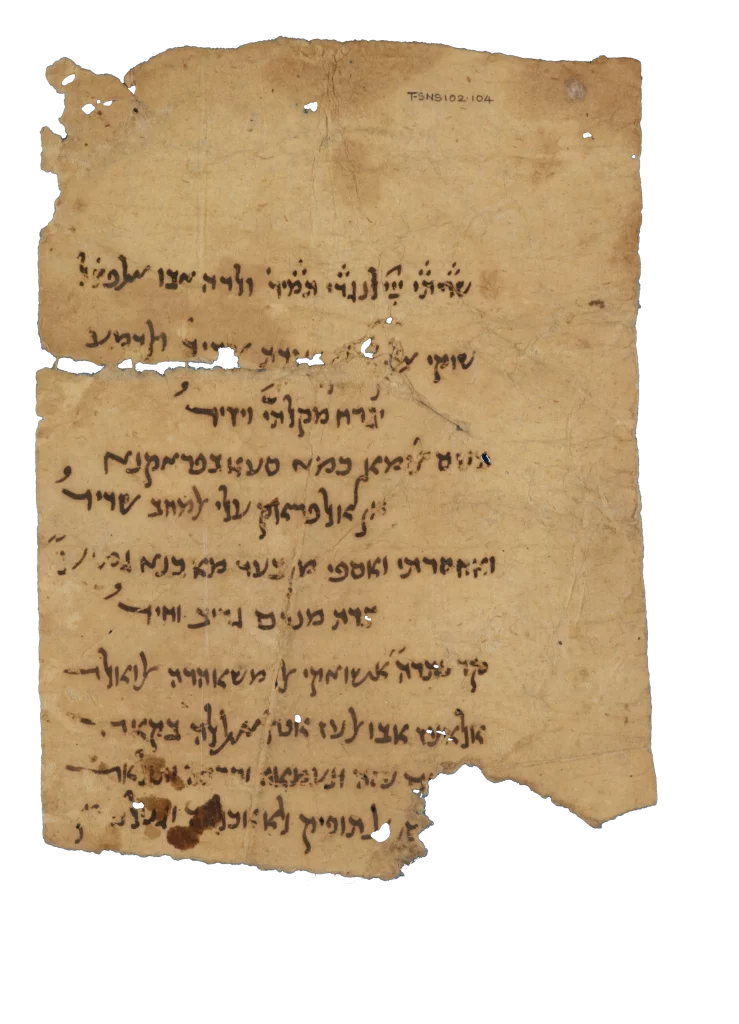

16. Cambridge University Library T-S NS 102.104

A poem taken from the book Alf layla wa-layla (“A Thousand and One Nights”)

Paper; Egypt (?); 11th–13th c.

The ever-popular Thousand and One Nights was enjoyed by the Jewish community too, as evidenced by a number of versions preserved in Judaeo-Arabic. This fragment is not a copy of the work, but of a poem that falls within it.

شوقي إليك [على الزمان جـ]ـديد والدمع

يجرح مقلتيَّ ويزيدُ

حشم الزمان كما سعا بفراقنا

إن الفراق على المحب شديدُ

My longing for you […] and tears

wound my eyes and even more.

Time is put to shame as it strives to separate us.

For the lover, most painful indeed is separation.

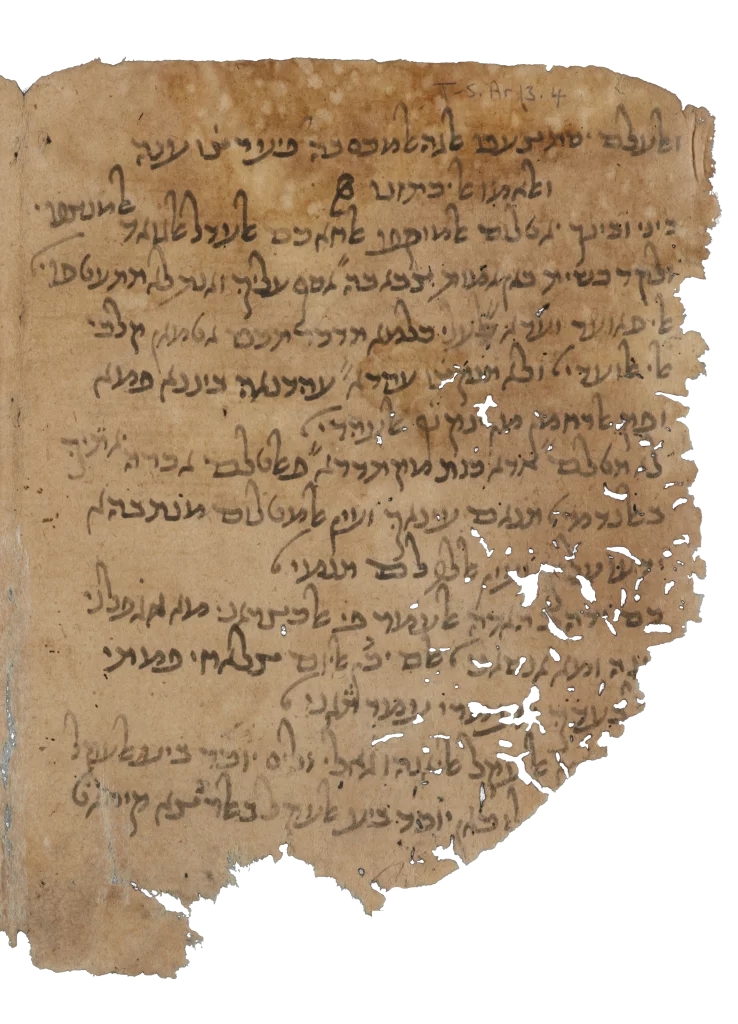

17. Cambridge University Library T-S Ar.13.4 (2 recto)

A poem belongs to Ali Ibn Abi Talib

Paper; Egypt or North Africa; 13th c. or later

Again, it is fascinating that such a poem as this one, ascribed to the cousin of the prophet Muḥammad, ʿAlī Ibn Abī, should be read and copied by a Jewish scribe in medieval Egypt.

لا تظلمن إذا ما كنت مقتدرا

فالظلم آخره يأتيك بالندم

تنام عينك والمظلوم مجتهدا

يدعو عليك وعين الله لم تنم

Do not oppress while you are able to do so.

Oppression brings to you, in the end, regret.

Your eyes fall asleep, and the eye of the oppressed stays awake.

He invokes (God) against you, and the Eyes of God never sleep.

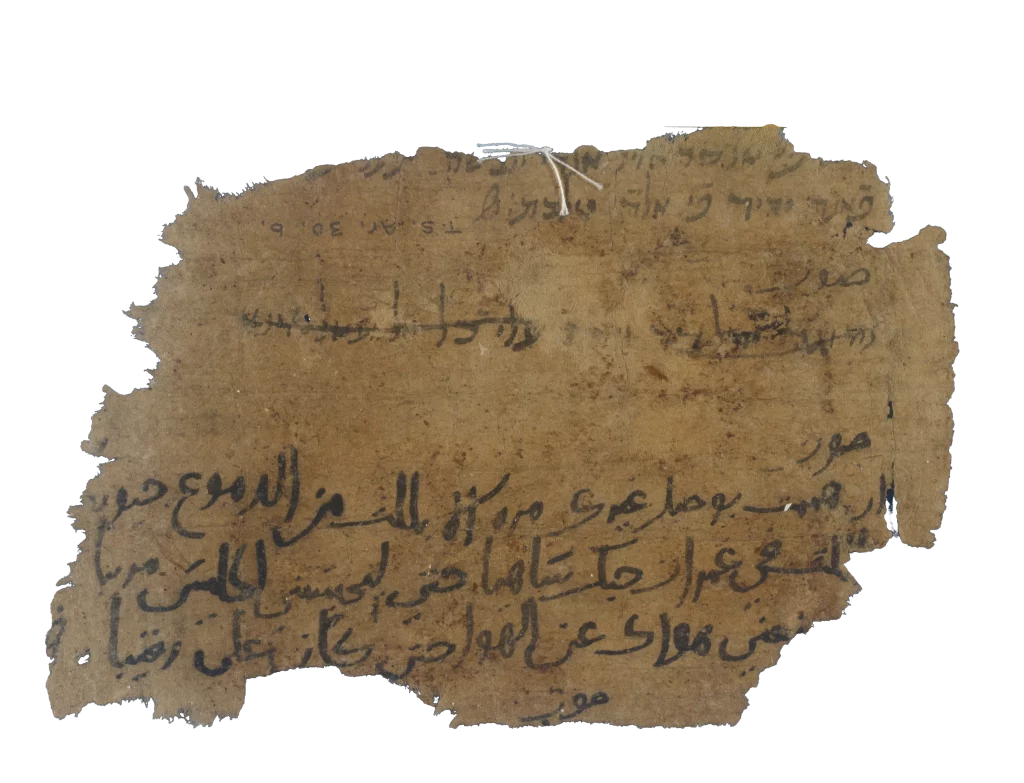

18. Cambridge University Library T-S Ar.30.6 (verso)

Love poem by Abū Firās al-Ḥamdānī (932–967 CE)

Paper; Egypt (?); 14th c. or later

This scrap contains poetry in Judaeo-Arabic and Arabic, and preserves part of a 10th-c. love poem by the Hamdanid poet Abū Firās.

حوت

[ ما ] ان هممت بوصل غيري مره الا بللت من الدموع جيوبا

[ وظلـ]ـلت في غمرات حبك ساهما حتى ليحسبني الجليس مريبا

[ إني ليمـ]ـنعني هواك عن الهوا حتى كأن علي (منك) رقيبا

It contains:

Once you turned to someone else, I soaked with tears my collars

I remained steeped in the depth of your love, so that people sitting nearby

thought that I was suspicious.

Your passion prevents me from [finding another] love, as if an observer [hired by you] watches me.

19. Cambridge University Library T-S Ar.37.127

Love poem by the Abbasid poet Ibn Abī Ḥuṣayna (998–1064 CE)

Paper; Egypt; 12th c. (?)

Again, showing that love poetry in particular was enjoyed throughout the Islamic world, this fragment preserves a Classical Arabic verse attributed to the mirdasid poet Ibn Abī Ḥuṣayna, transcribed in Hebrew script.

ولمّا اعتنقنا للوداع وقلُبها

وقلبي يفيضان الصبابة والوجد. بكت

لؤلؤاً رطباً ففاضت مدامعي عقيقاً

فصار الكل في نحرها عقداً

When we embraced to say farewell, at the moment that her heart

and mine were full of passion and love, she shed tears

of sprinkled pearls. My tears, subsequently, flooded with onyx.

At that point, everything (pearls and onyx) became a necklace on her neck.

Thank you!